Weather Forecasts May Help Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions From Nitrogen Fertilser

Increasing the sustainability credentials of agriculture extends to fertilizer applications, which works along the four R's; right product, right time,right rate and right place.Agriculture is responsible for up to 30 per cent of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions, according to a government coordinated report on farming and climate management.

Nitrous oxide (N2 O) is of particular concern for the industry because it has a global warming potential nearly 300 times that of carbon dioxide.

More than half of Australia’s N2 O emissions come from in-crop applied fertiliser. Under Australian conditions, N2 O emissions tend to be greatest when soils are warm and waterlogged and in paddocks with high carbon and nitrate content.

Adding nitrogen fertiliser to the soil before heavy rainfall is a recipe for increasing N2 O emissions. But can recent advances in dynamical weather forecasting be a cost-effective way to reduce N2 O emissions from nitrogen fertiliser?

This is the question now being asked by a team of researchers at the Queensland University of Technology (QUT), as part of the Managing Climate Variability (MCV) program’s ongoing research into climate forecasting for the Australian agricultural industry.

The QUT project is a partnership between the South Australian Research and Development Institute, the Bureau of Meteorology, and the Charles Sturt University campus at Orange.

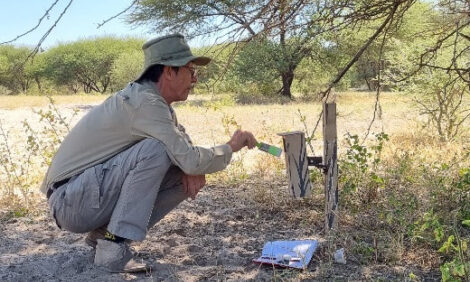

"Recent advances in the science, availability and communication of weekly and multi-week weather forecasts have unrealised potential in managing nitrogen fertiliser", says QUT’s Dr Clemens Scheer, who is heading the research project.

This unrealised potential, he explains, lies in more efficient use of nitrogen fertiliser.

"Farmers have long been advised, as part of best management practice, to avoid applying nitrogen fertiliser on moist soils before heavy rain", he says.

This becomes complicated, however, as farmers in dryland and regularly irrigated areas welcome the rain after top-dressing crops and pasture with fertiliser.

"The fertiliser industry is promoting the four Rs: right product, right rate, right time and right place", Dr Scheer says.

"Our project is focusing on using weather forecasts as a guide to help farmers make these decisions. We are using forecasts to adjust the timing, and in some cases, the rate of fertiliser application."

Researchers have found that a more efficient use of nitrogen fertiliser will not only have economic benefits by maximising plant uptake, but will also minimise N2 O emissions as well as other losses through denitrification, deep drainage and run-off.

The MCV project aims to develop a framework to study nitrogen fertiliser use in Australian farming systems and determine how weather and climate forecasts can be used to make better decisions.

The project will use a combination of climate simulation modelling and decision analysis. It will then apply the framework to case studies across the grains, dairy and sugar industries, and evaluate the framework’s impact on farm productivity and N2 O emissions.

"It’s all part of developing the information-rich, smart farming systems that are vital in the process of mitigating and adapting to climate change", Dr Scheer says.

"We will then be able to assess if using weather forecasts for nitrogen fertiliser decisions can also be the basis for an offset methodology for N2 O abatement under the federal government’s Carbon Farming Initiative."