The Life and Death of BSE

Fifteen years ago Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) was causing havoc in the EU. This fatal, neurodegenerative disease of cattle seemed both incomprehensible and unstoppable, but today many countries are looking to eradicate it once and for all, writes Adam Anson, TheCattleSite.The peak for BSE was registered in 1992 in the UK, when 36,680 cases were reported. Panic ensued when it was discovered that humans that ate infected cattle meat could develop an equally horrific variant of the disease known as new variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (vCJD). In all 4.4 million cattle were subsequently slaughtered during an eradication programme, but the long incubation period of the disease meant that it had time to hide in all corners of the world. Consequences of the epidemic are still being felt.

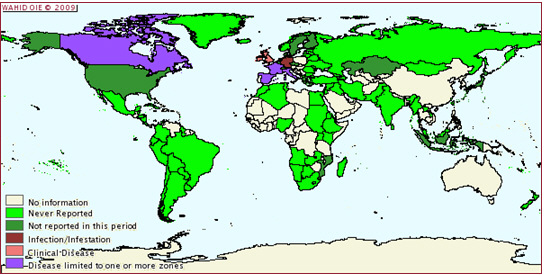

Since 1989, cases of BSE have been reported in Austria, Belgium, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Falkland Islands, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Oman, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United States. However, the BSE epidemic rapidly declined in the European Union (EU) immediately after 1992.

Even today the origin of this misfolded prion protein disease remains officially unknown, but a British enquiry concluded that the epidemic was most likely caused by feeding cattle meat and bone meal (MBM).

As understanding of the disease grows, the number of cases recorded across the world falls. According to figures from World Animal Health (OIE), in 2008 eleven countries identified cases of BSE in farmed cattle. The UK reported the most at 33, then Spain at 25. Ireland reported 23 cases, Portugal 18, France recorded eight and Canada reported four. In 2007, 15 countries reported cases of BSE, with one country -- the UK -- reporting 53 cases alone, but this is a far cry from the 36,682 recorded in 1992.

The EU Response

In 1994, the EU banned mammalian MBM to ruminants, however, the measures taken, the date of implementation and the extent of enforcement vary from country to country. In 2001, because of the continued risk from cross contamination, the EU introduced a total feed ban (e.g. ban on feeding MBM to all farm animals.

* "This is likely due to a reduction to the exposure of cattle to the BSE agent achieved through the implementation of the control measures taken" |

|

Ian Palombi, European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)

|

Across the EU cases of BSE have dropped rapidly, from around 2,200 in 2001 to about 100 in 2008.

According to Ian Palombi, European Food Safety Authority (EFSA): "This is likely due to a reduction to the exposure of cattle to the BSE agent achieved through the implementation of the control measures taken in EU."

Within the EU, 70 million cattle have been tested - in addition to those tested as BSE suspects - since 2001.

"Currently, at EU level, the age limit for BSE testing in the 15 old Members States is 48 months for healthy and at risk animals, whereas it is 24 months in at risk and 30 months in healthy cattle in the 12 “new” Member States," said Mr Palombi.

Monitoring programmes using newly developed tests were also quickly developed for the diagnosis of BSE in dead and slaughtered cattle throughout the EU. Use of these tests led to the first cases of BSE being detected in 12 countries.

EFSA also demands "compulsory removal and destruction of tissues containing the highest risk of BSE infectivity, such as the brain and spinal cord (Specified Risk Material) from bovine animals over a certain age." Following the detection of a positive BSE case, destruction of the carcass and culling strategies for herds with confirmed BSE cases.

The Rest of the World

While these stringent-but-costly precautions have helped to minimise the threat of BSE in Europe and helped regain beef market access in other parts of the world, other countries have been late to take such radical steps.

In February 2001, the US Government Accountability Office reported that the US Food and Drug Administration, responsible for regulating feed, had not adequately policed the various - and only partial - bans on MBM's. In 2003, Japan was the top importer of US beef, buying 240,000 tonnes valued at $1.4 billion, but after the discovery of the first case of BSE Japan stopped all US beef imports.

Over the years a total of 65 nations have implemented full or partial restrictions on importing US beef products because of concerns that US testing lacked sufficient rigour. Even today US beef has not reached the the same levels of export it achieved before BSE.

Canada and Japan have also been affected by this late recognition of BSE. Canada reported their first case in 2003 and Japan reported its first case in 2001. Both countries have reported cases of BSE in every subsequent year thereafter. It is likely that inadequate monitoring missed previous cases.

This year cattle producers of Ontario filed a C$10 billion class action law suit against the Canadian government in relation the mad cow disease outbreak in 2005. In Japan, a BSE testing programme, that has cost an estimated 1 trillion yen (approximately US$10 billion), has been questioned by top scientists for providing no benefit to consumers or the industry.

Many of the less developed countries across the world have never reported cases of BSE, but it is not certain if this is because there is no BSE present, or because the cases go unnoticed. Either way, insufficient safety measures mean that most are unable to export beef to the developed world.

The Future

Today BSE regulations are being reviewed once more, this time with the eye for reducing the economic burden which they hold over producers. A recent USDA Economic Research Service report studied the economic impact of BSE responses and regulations within the US.

"Meatpackers and renderers are among the first downstream users of cattle and beef products and byproducts affected during a major animal disease outbreak as regulations prohibit the entry of the meat of diseased animals into the food system," said the report.

"This results in supplies of raw materials (animals or meat) that cannot be disposed of through normal marketing channels. Policies and regulations implemented in the aftermath of a disease outbreak are often extensive, affect related industries, and have economic effects that last much longer than those of the disease outbreak."

According to the report many analysts have begun to ask about the tradeoffs between marginal reductions in these risks and the costs incurred in achieving these risk reductions. The Food Standards Agency of the UK also acknowledged the need for a "more proportionate, risk-based regime," with stepped changes to show "no loss of control."

The weight of BSE is finally beginning to evaporate. EFSA even predicts that as the incubation period finally comes to an end, BSE could be eradicated within the EU in a mere matter of years.

May 2009