Managing Cow Lactation Cycles

Poor feeding management of cows can lead to shorter, lower yielding lactations and increase calving interval. This report by John Moran from Asia Dairy Network explains the changing feed requirements of cows over the lactation cycle and how to match this with cow genetics.The lactation cycle

Cows must calve to produce milk and the lactation cycle is the period between one calving and the next.

The cycle is split into four phases, the early, mid and late lactation (each of about 120 days, or d) and the dry period (which should last as long as 65 d). In an ideal world, cows calve every 12 months.

A number of changes occur in cows as they progress through different stages of lactation.

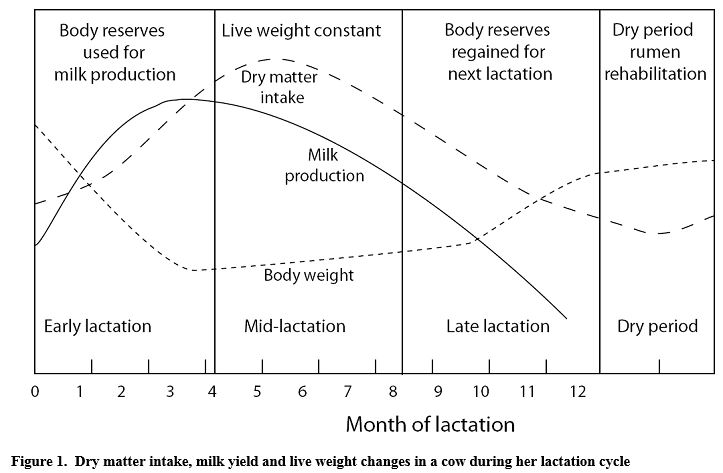

As well as variations in milk production, there are changes in feed intake and body condition, and stage of pregnancy. Figure 1 presents the interrelationships between feed intake, milk yield and live weight for a Friesian cow with a 14 month inter-calving interval, hence a 360 d lactation.

Following calving, a cow may start producing 10 kg/d of milk, rise to a peak of 20 kg/d by about 7 weeks into lactation then gradually fall to 5 kg/d by the end of lactation.

Although her maintenance requirements will not vary, she will need more dietary energy and protein as milk production increases then less when production declines. However to regain body condition in late lactation, she will require additional energy.

Cows usually use their own body condition for about 12 weeks after calving, to provide energy in addition to that consumed. The energy released is used to produce milk, allowing them to achieve higher peak production than would be possible from their diet alone.

To do this, cows must have sufficient body condition available to lose, and therefore they must have put it on late in the previous lactation or during the dry period.

From calving to peak lactation

Milk yield at the peak of lactation sets up the potential milk production for the year; one extra kg per day at the peak can produce an extra 200 kg/cow over the entire lactation.

There are a number of obstacles to feeding the herd well in early lactation to maximise the peak. The foremost of these is voluntary food intake.

At calving, appetite is only about 50 to 70 per cent of the maximum at peak intake. This is because during the dry period, the growing calf takes up space, reducing rumen volume and the density and size of rumen papillae is reduced.

After calving, it takes time for the rumen to “stretch” and the papillae to regrow. It is not until weeks 10-12 that appetite reaches its full potential.

Peak lactation to peak intake

Following peak lactation, cows' appetites gradually increase until they can consume all the nutrients required for production, provided the diet is of high quality. From Figure 1, cows tend to maintain weight during this stage of their lactation.

Mid and late lactation

Although energy required for milk production is less demanding during this period because milk production is declining, energy is still important because of pregnancy and the need to build up body condition as an energy reserve for the next lactation. It is generally more efficient to improve the condition of the herd in late lactation rather than in the dry period.

Dry period

Maintaining (or increasing) body condition during the dry period is the key to ensuring cows have adequate body reserves for early lactation.

If cows calve with adequate body reserves, they can cycle within two or three months after calving. If cows calve in poor condition, milk production suffers in early lactation because body reserves are not available to contribute energy.

In fact, dietary energy can be channelled towards weight gain rather being made available from the desired weight loss. For this reason, high feeding levels in early lactation cannot make up for poor body condition at calving.

Persistency of milk production throughout lactation

The two major factors determining total lactation yield are peak lactation and the rate of decline from this peak. In temperate dairy systems, total milk yield for 300 day lactation can be estimated by multiplying peak yield by 200.

Hence a cow peaking at 20 litres per day (L/d) should produce 4000 L/lactation, while a peak of 30 L/d equates to a 6000 L full lactation milk yield. This is based on a rate of decline of 7 to 8 per cent per month from peak yield, that is every month the cow produces, on average, 7 to 8 per cent of peak yield less than in the previous month.

This level of persistency is the target for well managed, pasture-based herds in temperate regions.

Actual values can vary from 3 to 4 per cent per month in fully fed, lot fed cows to 12 per cent or more per month in very poorly fed cows, for example during a severe dry season following a good wet season in the tropics.

The rate of decline from peak, or persistency, depends on:

• peak milk yield

• nutrient intake following peak yield

• body condition at calving

• other factors such as disease status and climatic stress

Generally speaking, the higher the milk yield at peak, the lower its persistency in percentage terms.

Underfeeding of cows immediately post-calving reduces peak yield but also has adverse effects on persistency and fertility. Dairy cows have been bred to utilise body reserves for additional milk production, but high rates of live weight loss will delay the onset of oestrus.

Underfeeding of high genetic merit cows in early lactation is one of the biggest nutritionally induced problems facing many small holder farmers in the humid tropics, because they often do not have the necessary improvements in feeding systems to utilise high genetic potential.

If imported high genetic quality cows are not well fed, milk production is compromised, but of more importance, they will not cycle until many months post-calving.

Theoretical models of lactation persistency

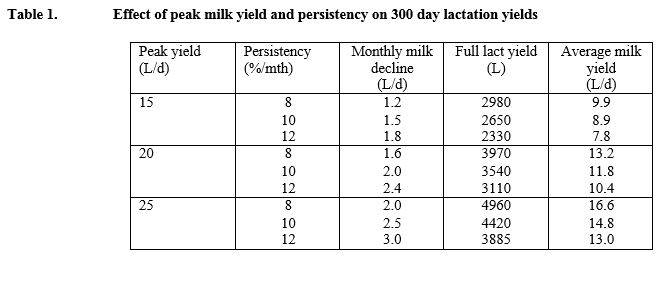

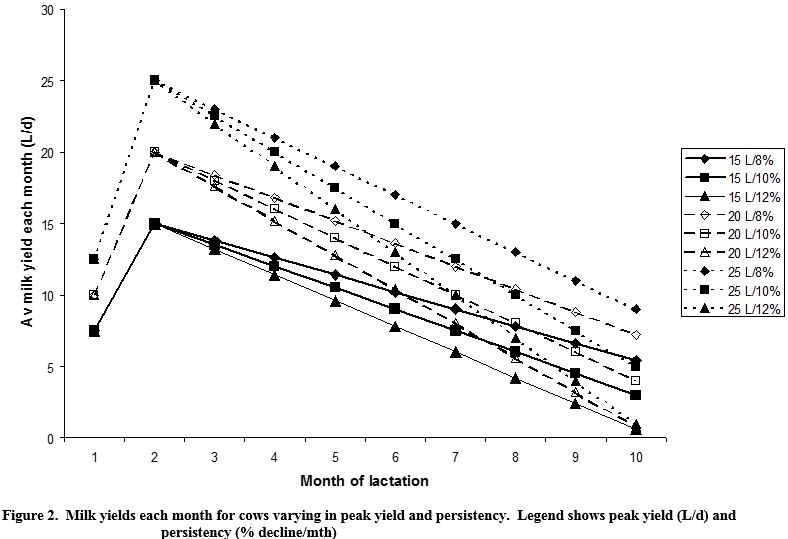

Table 1 and Figure 2 present data for milk yield over 300 day lactations in cows with various peak milk yields and lactation persistencies.

Such data provides the basis of herd management guidelines for dairy systems with 12 month calving intervals. Depending on herd fertility, hence target lactation lengths, similar guidelines could be developed for 15 or 18 month calving intervals.

Table 1 and Figure 2 only present data for cows with peak yields of 15, 20 and 25 L milk/day.

Small holder dairy farms in the humid tropics with good feeding and herd management should be able to achieve 15 L/day peak yield, and for those with high genetic merit cows, 20 or 25L/day is realistic.

Lactation persistencies of less than 8 per cent per month may be achievable in tropical dairy feedlots but more realistic persistencies are the 8 to 12 per cent per month presented in the Table 1 and Figure 2.

Virtually every small holder farmer records daily milk yield of his or her cows, so they know peak yield and can easily determine the monthly rate of decline, providing a simple monitoring tool to assess their level of feeding management.

Unless feeding management can be improved, it may be better in the long run to import cows of lower genetic merit.

For example, importers may request “5000 L cows” (that is cows that peak at 25 L/day under good feeding management, with a persistency of 8 per cent/mth).

If, through poor feeding, their persistency is reduced to 12 per cent per month, 300 d lactation yields are only 3900 L and they do not cycle for many months after calving, “4000 L cows” may be a better investment. From Table 1, such cows would produce similar milk yields if they could be fed to 8 per cent per month milk persistency and they are more likely to cycle earlier.

Impacts of short lactation length

Poor feeding management of potentially high yielding cows can create many problems.

Lactation anoestrus can occur as the cows are forced to utilise more of their body reserves in early lactation. This can lead to low peak milk yields and shortened lactation lengths.

Cows will dry off prematurely if they receive insufficient feed nutrients to maintain viable processes of milk production in their mammary tissue.

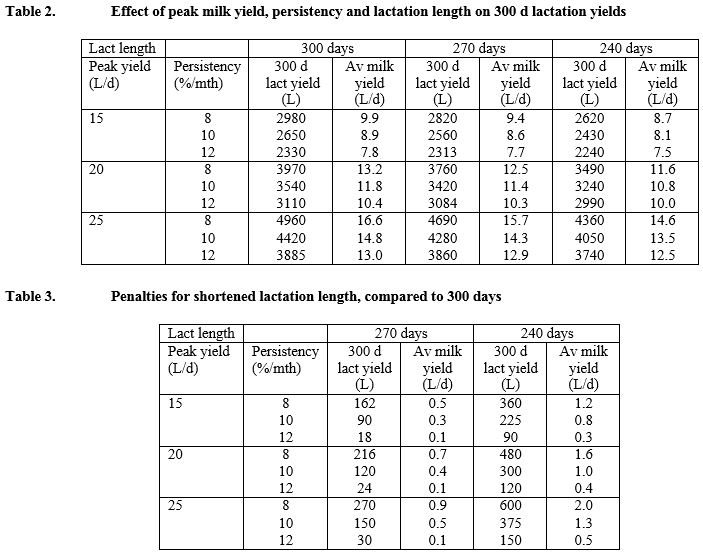

The impact of decreasing lactation lengths on 300 day lactation milk yields and average daily milk yields are presented in Table 2. These data are based on the same persistency data used in Table 1. The penalties for these shortened lactation lengths are presented in Table 3.

Compared to 10 month lactations, inherently poor yielding cows with low peak milk yields can lose 20 to 160 L milk through only 9 months milking or 90 to 360 L milk if only milking for 8 months.

Following higher peak milk yields, this will increase to penalties of 30 to 270 L milk for 9 month to 120 to 600 L for 8 month lactation lengths. This can have a big effect on the herd’s rolling herd average which can be reduced by 0.3 to 2.0 L/cow/day for the extreme values presented in Table 2 and 3.

These tables are based on 300 day lactation lengths, that is under an ideal situation where cows calve down every 12 months.

Inter-calving intervals are more likely to be 13, 14 or 15 months, hence lactation lengths should be even longer than 300 days.

Ideally cows should be managed to have a two month dry period to allow the mammary tissue to recuperate before the next lactation. However, lactation lengths of just 8 months followed by dry periods of another 8 months are all too common in many tropical small holder dairy farms. This then equates to only 50 per cent of the adult cows milking at any one time.