How have livestock evolved to deal with extreme climates?

New research from the RVC explores the genetic adaptions and evolution of livestock and wild animals in response to extreme climates.New research from the Royal Veterinary College (RVC) and the Institute of Cytology and Genetics in Novosibirsk, Russia has identified the genetics of extreme climate adaptation which help the world’s most northern Yakut cattle population in Siberia survive their extreme cold environment. This work, published in Molecular Biology and Evolution, paves the way for a greater understanding of how livestock and wildlife are co-evolving to adapt to climate change.

While the origins of Yakut cattle are unknown, this population, which can be found up to 200km above the Polar Circle and survive temperatures as low as -70 degrees Celsius, has had little interbreeding with other cattle populations, or closely related species such as yak, bison and guar.

With their last common ancestor traced to European cattle breeds from approximately 5,000 years ago, researchers have surmised that the adaptations to extreme cold climates found in Yakut cattle are mostly derived from their own genetics. It was also found that Yakut cattle share many genetic variants which are similar to those found in Asian and African cattle breeds, but not those found in Europe.

The research, led by Dr Denis Larkin, Reader in Comparative Genomics at the RVC, also found that these genetic variants likely represent the ancestral alleles, or variant form of genes, that have been lost in European cattle due to human selection and breeding for milk and meat production. However, retaining these variants has enabled Yakut cattle to adapt to changing environment conditions and extreme cold. The findings also suggest that the same genetic variants could help cattle breeds in Asia and Africa to adapt to their own challenging climates.

Dr Denis Larkin, Reader in Comparative Genomics at the RVC and who led this research, said

“This study is a breakthrough because it shows for the first time that convergent evolution acts not only at the species level but on the human-made breeds as well. It is amazing to see that exactly the same amino acid change has formed and become nearly fixed in a single breed of cattle adapted to extreme environment and 16 species of mammals.”

While sharing some traits with Asian and African counterparts, one finding did differentiate Yakut cattle – the presence of one specific high-frequency coding nucleotide variant, which changes protein features. This particular variant was not found in any of the more than 100 other sequenced cattle breeds, nor the ancient DNA samples from closely related species from Siberia, excluding possibility of introgression.

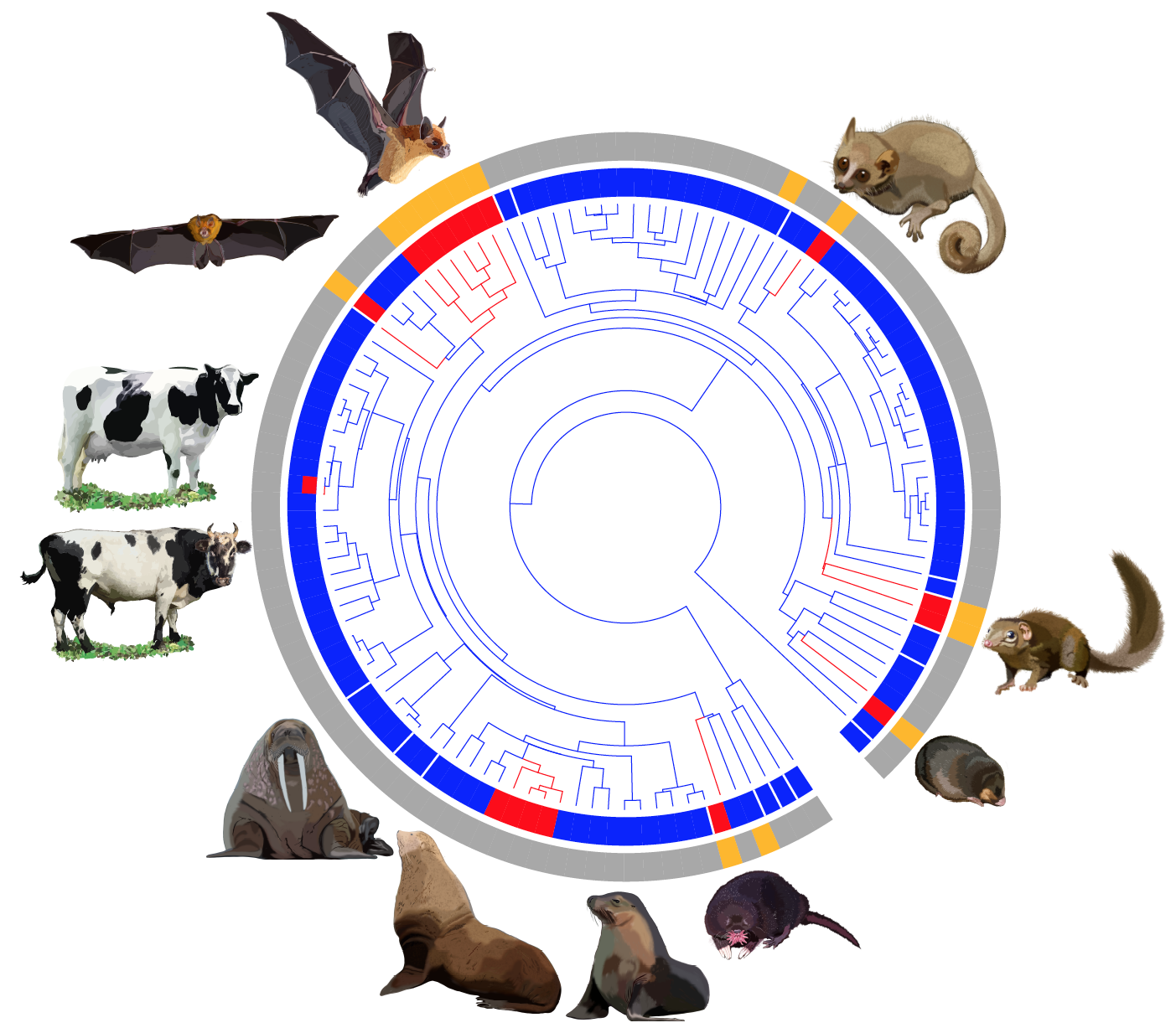

This mutation affects a highly evolutionary conserved position in the nebulin-related-anchoring protein (NRAP), which links actin filaments in muscles, including heart muscle. Interestingly, from the more than 100 mammals studied, only 16 species displayed the same change, likely enabling them to hibernate, enter torpor, deep dive or adapt to the cold.

Convergent evolution at the same nucleotides is rare and, before this study, were reported for different species only. For example, in bats and dolphins the same mutation is present in a gene involved in echolocation, while multiple fish species have a mutation in the protein called rhodopsin, to adapt to different marine and freshwater light conditions.

This research suggests however, that a convergent evolutionary change has occurred at the same nucleotide of the NRAP gene in many cold-adapted species and a single northernmost cattle breed. It has therefore discovered that convergent evolutionary changes can form quickly in breeds of domesticated species, likely providing them with features absent from the rest of the species.

Dr Laura Buggiotti, Bloomsbury SET Innovation fellow at the RVC and first author on the paper, said

“The Yakut cattle still holds a lot of mysteries but now we know it is very close to the ancestral cattle population and contain genetics which made them adaptable to extremely cold temperatures. This is something we need to pass to other breeds to be able to survive climate changes”.

There are multiple studies showing that NRAP is involved in climate adaptations in mammals, reptiles, and even fish. However, this research has now discovered that it is involved in adaptation to cold climates in the Yakut cattle as well.

Interestingly, work on humans and mice shows that mutations in NRAP cause cardiomyopathy, a disorder when pumping ability of the heart is altered. Dr Larkin and Dr Laura Buggiotti, Bloomsbury SET Innovation fellow at the RVC, hypothesize that a similar mechanism could help the heart in cold adapted and deep diving species, pumping blood more efficiently when it is cold.

Given the growing body of research highlighting the link between climate change and extreme weather, the research could mark an important step in mitigating the worst effects of extreme cold in the context of livestock farming.