CattleFax at NCBA: US weather outlook for 2022 tentatively signals continuation of La Niña, droughts

Anyone with a smartphone has access to weather forecasts. But short-term predictions are one thing; anticipating global weather patterns is another.Part of Series:

< Previous Article in Series Next Article in Series >

Anyone with a smartphone has access to weather forecasts. But short-term predictions are one thing; anticipating global weather patterns is another.

As we emerge from a year of unprecedented drought, many producers are hoping for improved conditions in 2022. During the recent National Cattleman's Beef Association, CattleFax asked Matt Makens of Makens Weather to share recent trends and offer high-level predictions for the rest of the season.

La Niña: the elephant in the room

When building forecasts, Makens and his team rely on data from analog years to predict current trends.

“I start going back in time and find similar events historically,” he said. “I whittle that list down even more, and usually try to get 5-7 best-fit years for seasonal forecasts.”

Critical steps in this process include:

- Finding the critical boxes of ocean & atmospheric temperatures

- Running statistical analysis to identify historical analogs

- Breaking down the list to make predictions for the rest of the year

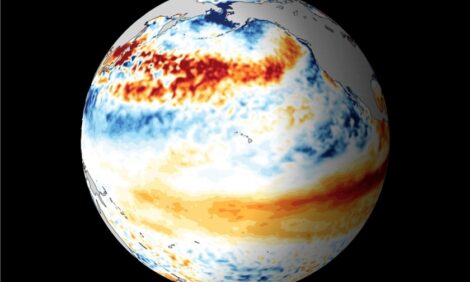

The biggest question on people’s minds regards the La Niña-El Niño cycle: will we continue with La Niña for a third straight year or will we switch to El Niño? Right now, the answer is up in the air because these storm cycles generally ramp up in the spring, then taper off in the summer, so Makens said it’s still too early to make a definite prediction.

A third consecutive La Niña is unlikely, but it has happened in the past. Ocean temperatures are fluctuating, meaning that either a third La Niña or a return to El Niño is a foreseeable scenario.

The prediction challenge is that there are no analogs for some of the current trends, particularly colder temperatures in the Gulf of Alaska, the US West Coast and Western Canada. Although the Atlantic is very warm and sends a lot of tropical moisture into the eastern US, these cold temperatures inevitably result in drier systems hitting the Atlantic. This would seem to indicate another La Niña.

At some point, however, the warm waters from Hawaii to Southeast Asia will be forced back across the east, which will replace our La Niña with El Niño. The transition hasn’t begun yet, but it will happen in the near future.

Makens’ prediction right now: “All options are still on the table.” The most likely scenario, however, is a departure from the El Niño-La Niña pattern, and into a more neutral pattern.

However, there’s a notable exception to that prediction. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predicts that La Niña will continue for a third year. In that case, then current oceanic conditions will continue into the spring—with colder than average conditions.

Assuming another La Niña, what does that mean?

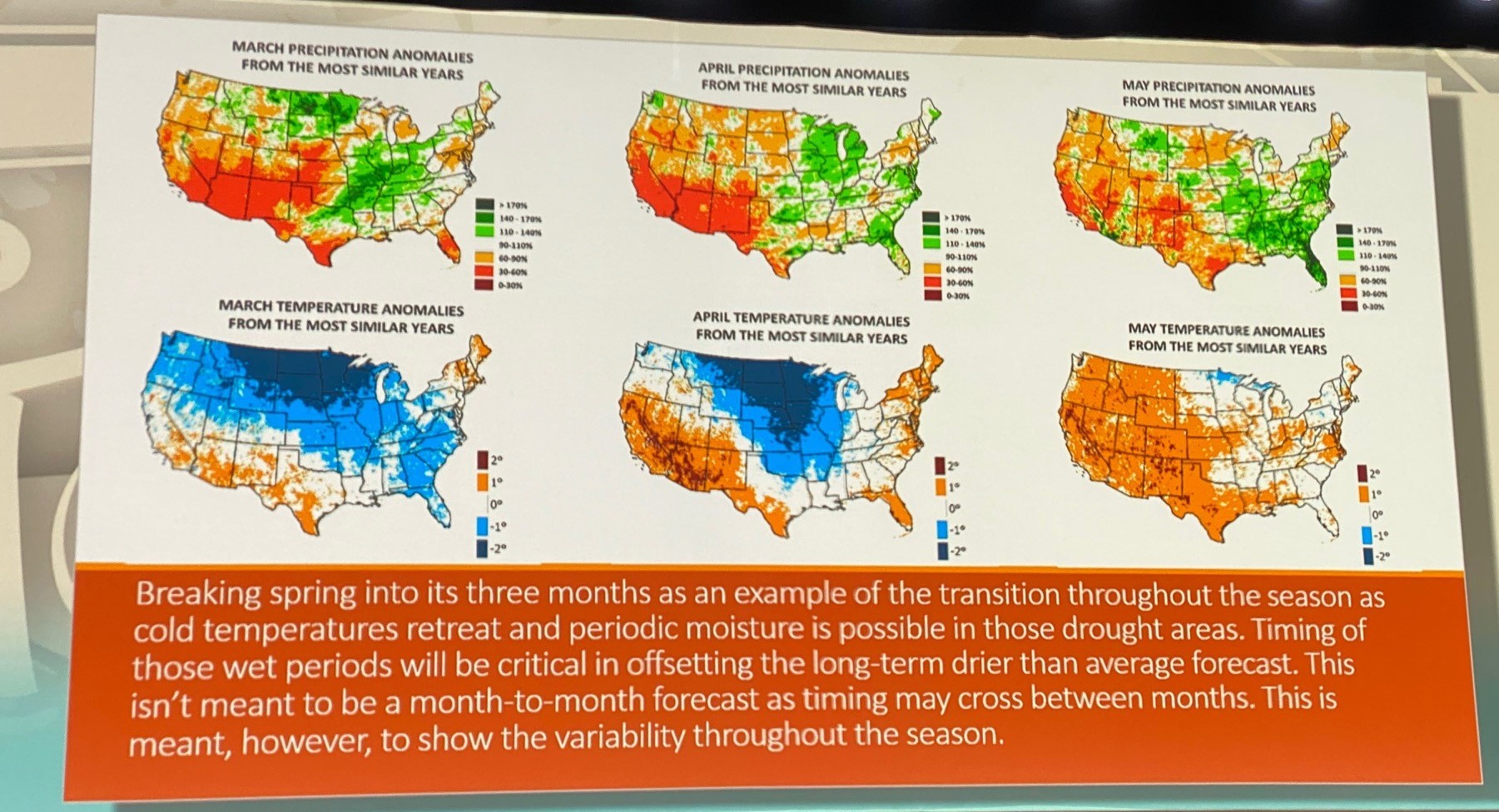

If NOAA’s modeling is correct and 2022 will be another La Niña this year, what will that mean for the US and the rest of the western hemisphere? The biggest impact will be that the southern regions will continue to experience plenty of water, while the northern regions—primarily Colorado down to West Texas—will continue experiencing drought.

This is evidenced by the monsoon that appears to be active in Mexico this year. Generally, an active monsoon in the south means the Corn Belt will be dry. This is why the timing of these precipitatory events is critical—too much water in the south means the north will experience another drought in 2022.

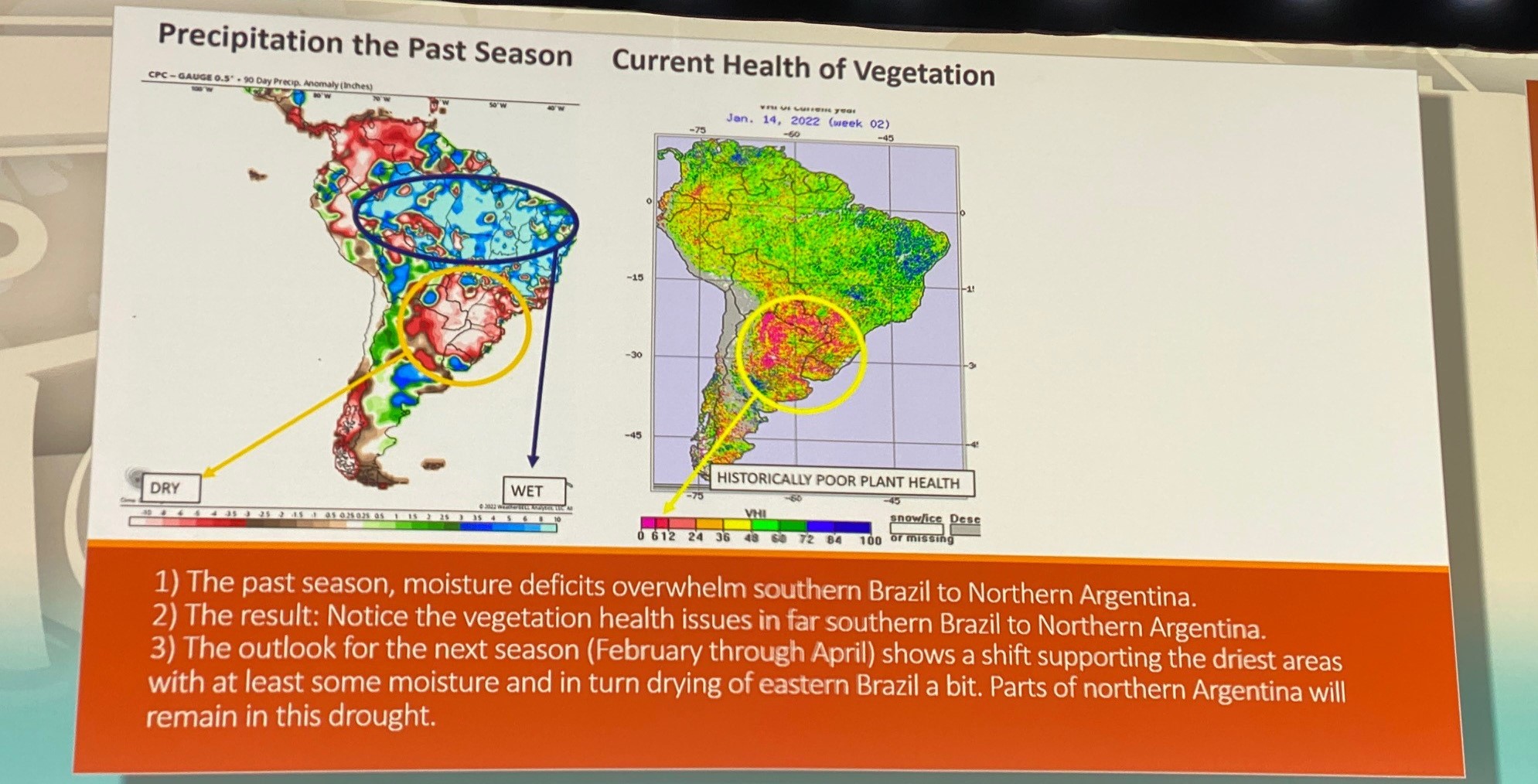

Impact of La Niña on vegetation

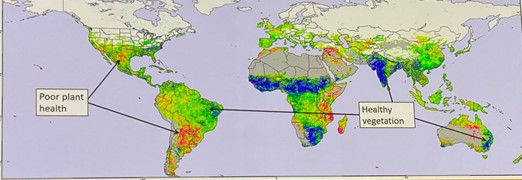

Given these events, vegetation is going to be an important topic of conversation. According to the vegetation index, there’s a mix of good and poor vegetation in the Western hemisphere. Northern Brazil, for instance, has an overall very wet pattern and healthy vegetation, while Southern Brazil and Northern Argentina are experiencing the poorest vegetation they’ve seen in 40 years.

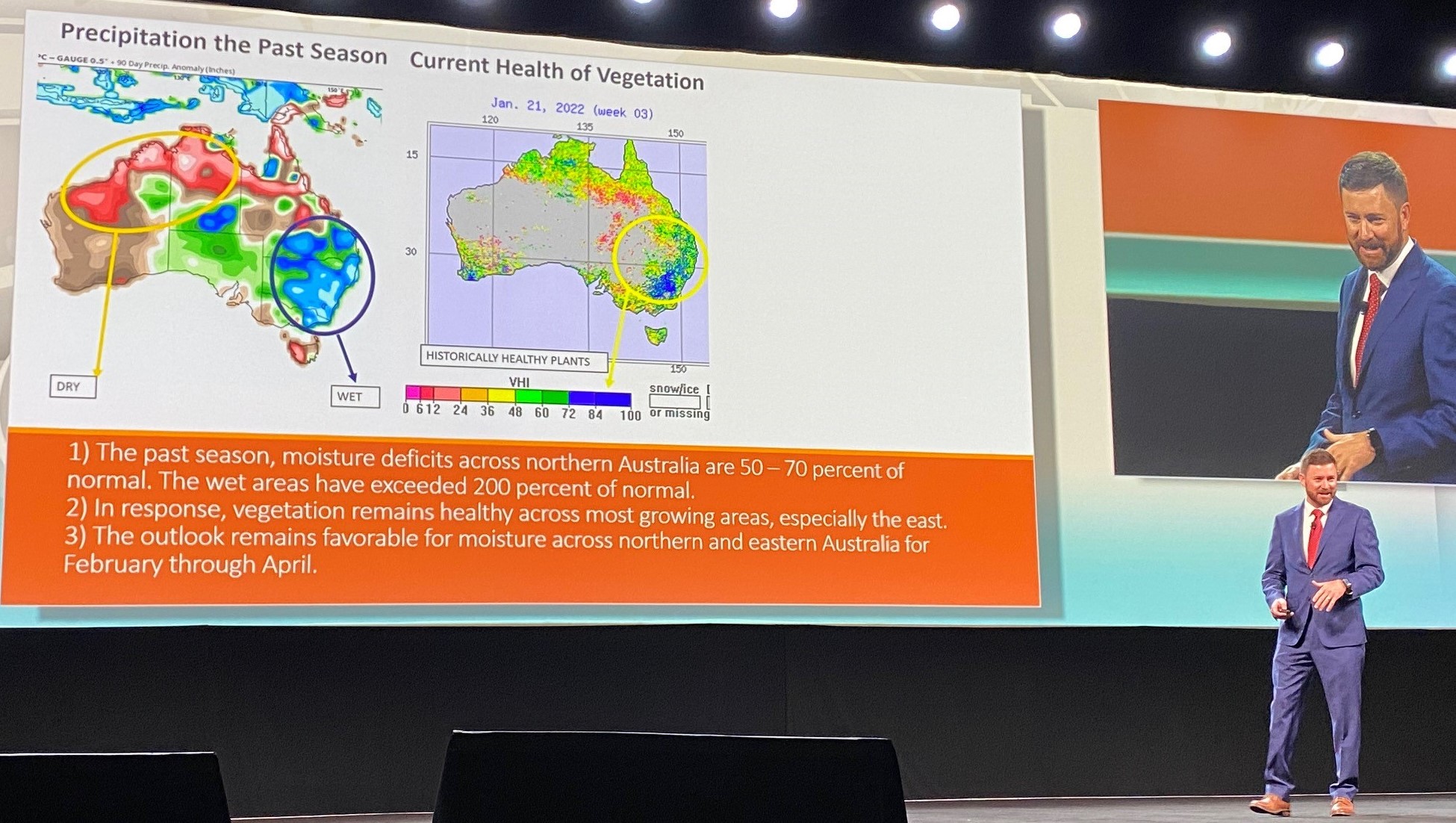

In Australia, the eastern side of the continent has had 200% of normal wetness, with the north seeing 50-75%, a major shift from a poor year in 2021.

Finally, the US has seen a wet season, but not incredibly wet. There has been hit-and-miss moisture in the Tennessee and Ohio Valleys, and some in the Upper Midwest. However, across the South, vegetation has struggled.

However, given the historic nature of the current drought, vegetation is faring far better than we would have expected. This provides a glimmer of hope, that even if drought continues, producers are prepared to make the most of a bad situation.